Who and How Did The First Humans Get To Utah?

- Travis Uresk

- Nov 3

- 68 min read

| by Travis Uresk | November 3rd, 2025 |

Archaeological studies indicate that human colonization of North America by the Clovis culture dates back more than 13,000 years. Recent evidence suggests that people may have been on the continent around 14,700 years ago—and possibly even several millennia before that.

The conventional view has been that the first migrants who populated the North American continent arrived across an ancient land bridge from Asia once the enormous Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets receded, creating a passable corridor nearly 1,000 miles long that emerged east of the Rocky Mountains in present-day Canada.

Evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev, however, believed that one aspect of the conventional theory required further investigation. "What nobody has looked at is when the corridor became biologically viable," says Willerslev, director of the Center for Geo Genetics at the University of Copenhagen. "When could they actually have survived the long and difficult journey through it?"

A pioneer in the study of ancient DNA, Willerslev led the first successful sequencing of an ancient human genome and specializes in extracting ancient DNA from plant and mammal remains in sediments to reconstruct ancient history. According to a recent profile in the New York Times, "Willerslev and his colleagues have published a series of studies that have fundamentally changed how we think about human history," and a new study published in the journal Nature, co-authored by Willerslev, may lead to a rethinking of how Ice-Age humans first arrived in North America.

The study's international team of researchers traveled to the Peace River basin in western Canada in the dead of winter, a spot that, based on geological evidence, was among the last segments along the 1,000-mile corridor to become free of ice and passable. At this crucial chokepoint along the migration path, the research team took nine sediment cores from the bottoms of British Columbia's Charlie Lake and Alberta's Spring Lake, remnants of a glacial lake that formed as the Laurentide Ice Sheet began to retreat between 15,000 and 13,500 years ago.

After examining radiocarbon dates, pollen, macrofossils, and DNA from the lake sediment cores, the researchers found that the corridor's chokepoint was not "biologically viable" for sustaining humans on the arduous journey until 12,600 years ago—centuries after people were known to have been in North America. Willerslev's team found that, until then, the bottleneck area lacked the basic necessities for survival, such as wood for fuel, tools, and game animals for hunters to hunt.

From the core samples, the researchers discovered that steppe vegetation first appeared in the region 12,600 years ago, followed quickly by the arrival of animals such as bison, woolly mammoths, jackrabbits, and voles. Around 11,500 years ago, a transition occurred to a more densely populated landscape, characterized by trees, fish such as pike and perch, and animals including moose and elk.

The research team used a technique called "shotgun sequencing" to test the samples. "Instead of looking for specific pieces of DNA from individual species, we basically sequenced everything in there, from bacteria to animals," Willerslev says. "It's incredible what you can get out of this. We found evidence of fish, eagles, mammals, and plants. It demonstrates the practicality of this approach in reconstructing past environments.

“The bottom line is that even though the physical corridor was open by 13,000 years ago, it was several hundred years before it was possible to use it," Willerslev says. "That means that the first people entering what is now the U.S., Central, and South America must have taken a different route. Whether you believe these people were Clovis or someone else, they simply could not have come through the corridor, as long claimed."

“There is compelling evidence that Clovis was preceded by an earlier and possibly separate population, but either way, the first people to reach the Americas in Ice-Age times would have found the corridor itself impassable,” adds study co-author David Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University.

While later groups may have used the passageway across the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska, the study's authors suggest that the first humans in North America likely migrated along the Pacific coast; however, the precise route remains unknown.

“The route taken by the first humans coming to America is still unknown, but much evidence points to the Pacific coast," named the "Kelp Highway, says study co-author Mikkel Winther Pedersen, a Ph.D. student at the Center for Geo Genetics at the University of Copenhagen. "If this is the case, we could be looking at humans who adapted to survive by exploiting the marine resources, whether by boat or from sea ice. They could have had a subsistence resembling what the Inuit have had."

In recent decades, archaeologists have uncovered strong evidence that the earliest migrations from Siberia took place when Asian explorers in small boats skirted the Pacific Coast as they moved south. Glaciers and ice fields that developed during the Pleistocene era still blocked overland routes through the center of the North American continent. Beginning roughly 17,000 years ago, however, melting glaciers along the Pacific Coast opened a marine route for migration.

The Kelp Highway was named in recognition of the vast and productive kelp forests that extended from what is now Alaska to Baja California, and then sporadically through Central America and along the coast of South America. The cold ocean currents flowing along these coasts were home to hundreds of species of edible plants and animals that could provide ample and dependable resources for the people traveling south. These earliest explorers would have relied primarily on the bounty of the sea, essentially making a living as marine hunter-gatherers, while also foraging for food on land. The similarity of the ecosystems they encountered over thousands of miles surely made their explorations easier as they moved southward.

The Kelp Highway was named in recognition of the vast and productive kelp forests that extended from what is now Alaska to Baja California, and then sporadically through Central America and along the coast of South America. The cold ocean currents flowing along these coasts were home to hundreds of species of edible plants and animals that could provide ample and dependable resources for the people traveling south. These earliest explorers would have relied primarily on the bounty of the sea, essentially making a living as marine hunter-gatherers, while also foraging for food on land. The similarity of the ecosystems they encountered over thousands of miles surely made their explorations easier as they moved southward.

This new evidence, coupled with paleoecological studies of Beringia's ice-age environment, led to the Beringian Standstill hypothesis. To some geneticists and archaeologists, the area around the Bering Land Bridge is the most plausible place where the ancestors of the first Americans could have been genetically isolated and become a distinct people. They believe such isolation would have been virtually impossible in southern Siberia, or near the Pacific shores of the Russian Far East and around Hokkaido in Japan—places already occupied by Asian groups.

As scientists examined more archaeological sites and as they developed better dating methods, the puzzle pieces of this “Clovis-First” model gradually fell apart. Foremost among the new findings are accurately dated occupation sites that have ages several thousand years older than the Clovis sites. And some of these extremely old settlement sites are near the southern tip of South America.

Along the Pacific coast of North and South America, archaeologists continue to search for more evidence of early migrations on the Kelp Highway. They have found pre-Clovis occupation sites from Vancouver Island in Canada to northern California, offshore from southern California in the Channel Islands, in Baja California, and coastal Peru and Chile. Many more coastal lowland occupation sites surely disappeared when sea level rose as glaciers and ice fields melted at the end of the Pleistocene. Landscape changes from tsunamis, earthquakes, and coastal erosion have also obscured ancient habitation sites.

“The whole-genome analysis—especially of ancient DNA from Siberia and Alaska—really changed things,” says John F. Hoffecker of the University of Colorado’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. “Where do you put these people where they cannot be exchanging genes with the rest of the Northeast Asian population?”

Could humans have even survived at the high latitudes of Beringia during the last ice age, before moving into North America? This possibility has been buttressed by studies showing that large portions of Beringia were not covered by ice sheets and would have been habitable as Northeast Asia emerged from the last ice age. Scott Elias, a paleoecologist with the University of Colorado's Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, used a humble proxy—beetle fossils—to piece together a picture of the climate in Beringia 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. Digging in peat bogs, coastal bluffs, permafrost, and riverbanks, Elias unearthed skeletal fragments of upwards of 100 different types of tiny beetles from that period.

“People could have made a pretty decent living along the southern coast of the land bridge, especially if they had knowledge of marine resource acquisition,” says Elias. “The interior in Siberia and Alaska would have been very cold and dry, but there were large mammals living there, so these people may have made hunting forays into the adjacent highlands.”

So who were the first Americans, and how and when did they arrive?

Genetic studies suggest that the first people to arrive in the Americas descended from an ancestral group of Ancient North Siberians and East Asians, who mixed around 20,000 to 23,000 years ago. They crossed the Bering Land Bridge sometime between then and 15,500 years ago, said David Meltzer, an archaeologist and professor of prehistory in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and author of the book "First Peoples in a New World, 2nd Edition" (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

But some archaeological sites hint that people may have reached the Americas far earlier than that.

For instance, there are fossilized human footprints in White Sands National Park in New Mexico that may date back 21,000 to 23,000 years. That would mean humans arrived in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum, which occurred between about 26,500 and 19,000 years ago, when ice sheets covered much of what is now Alaska, Canada, and the northern U.S.

Almost all scientists agree, however, that this incredible journey was made possible by the emergence of Beringia — a now-submerged, 1,100-mile-wide landmass that connected what is now Alaska and the Russian Far East. During the last ice age, much of the Earth's water was frozen into ice sheets, resulting in lower ocean levels. Beringia emerged once the waters of the North Pacific dropped roughly 164 feet below today's levels; it was passable on foot between 30,000 and 12,000 years ago, according to a 2021 review in the journal Nature by Meltzer and Eske Willerslev, a geneticist at the University of Cambridge.

From there, the archaeological picture gets muddier. The older version of the story originated in the 1920s and 1930s, when Western archaeologists discovered sharp-edged, leaf-shaped stone spear points near Clovis, New Mexico. The people who made them, now dubbed the Clovis people, lived in North America between 13,000 and 12,700 years ago, according to a 2020 analysis of bone, charcoal, and plant remains found at Clovis sites.

At the time, it was thought that the Clovis traveled across Beringia and then moved through an ice-free corridor, or "a gap between the continental ice sheets," in what is now part of Alaska and Canada, Davis, who leads excavations at an ancient North American site in Cooper's Ferry, Idaho, told Live Science.

"Once they exited, they spread quickly throughout the Americas, bearing a signature stone tool known as the Clovis spear point," which was likely used to hunt animals such as mammoths and bison, as well as smaller game. For decades, it was difficult to argue that the first Americans arrived before 13,000 years ago.

However, new discoveries began to slowly turn back the clock on the arrival of the first Americans. In 1976, researchers discovered the site of Monte Verde II in southern Chile, which radiocarbon dating showed to be about 14,550 years old. It took decades for archaeologists to accept the dating of Monte Verde, but soon, other sites also pushed back the date of humans' arrival in the Americas.

The Paisley Caves in Oregon contain human fossilized poop, dating back about 14,500 years. Page-Ladson, a pre-Clovis site in Florida with stone tools and mastodon bones, dates to about 14,550 years ago. And Cooper's Ferry — a site that includes stone tools, animal bones, and charcoal — dates to around 16,000 years ago.

There are dozens more sites, although some of the older ones are controversial. For instance, some archaeologists claimed that 31,500-year-old rocks in a remote Mexican cave were evidence of stone tools made by humans, but a rebuttal argued that the rocks formed naturally. Another site in Brazil holds giant sloth bones that may have been modified by humans at least 25,000 years ago, but a narrow hole in the bones could have formed naturally, Davis told Live Science. And 50,000-year-old stone tools at Pedra Furada in Brazil may have actually been made by capuchin monkeys, a 2022 study in the journal The Holocene found.

Contextual Usage

Uinta: Used for natural geographical features, including:

Uinta Mountains

Uinta River

Uinta National Forest

Uintah: Used for political or man-made entities, including:

Uintah County

Uintah School District

Uintah Indian Reservation

Who Reached Utah first?

Archaeologists have identified several variants of the Fremont culture, associated with specific geographical regions in Utah, including the Great Salt Lake, Sevier, Parowan, San Rafael, and Uinta. Members of these geographical variants of the culture developed or adopted various agricultural, architectural, and other cultural elements at different times, further distinguishing the several culture variants.

The Fremont people occupied the Uinta Basin around 600 A.D. The Fremont people occupied the Uinta Basin sometime later, around 600 A.D. Then, other Fremont people occupied different areas of the Great Basin region. The Uinta Fremont cultivated corn and other plants later than did people of the two southern Utah Fremont culture variants. The area's geographical isolation may have been the primary reason the Fremont people later occupied the Uinta Basin; the climate and availability of other resources may explain their later cultivation of corn and other plants.

The architecture of the Uinta Fremont was also different from that of other Fremont cultures. The Uinta Fremont constructed shallow, saucer-shaped pit houses or surface structures with off-centered fire pits. Surface storage structures were generally absent. Unique to the Uinta Fremont people was their use of Gilsonite to repair their clay wares.

The many Fremont Indian sites in Duchesne County and the Uinta Basin, including rock art panels, have provided significant information and contributed to a growing body of knowledge about the Fremont people. Archaeologists have identified phases within the Uinta Fremont variant. These are commonly known as the Cub Creek and Whiterocks phases, and they generally differ in the adoption of corn, the use of pottery, and other cultural, economic, and architectural characteristics.

The most significant Fremont cultural sites in the county are in Nine Mile Canyon on the Duchesne-Carbon county line. Archaeologists have identified and investigated nearly 300 archaeological sites in the Nine Mile Canyon area, with additional sites still being discovered from time to time.

A recent, extensive study by archaeologists indicates that the Tavaputs Fremont people adapted well to the Tavaputs Plateau's geography and natural resources. Late in arriving at the plateau country, the Tavaputs Fremont Indians adopted dry-laid masonry in the construction of their structures. They were also heavily concentrated in canyon drainages, which provided the best local environmental conditions for raising corn. They lived in the rugged Tavaputs Plateau country on a short-term or seasonal basis.

Elsewhere in the county, the Fremont people developed a simple irrigation system to water their small gardens of corn, squash, and beans. In some places, their irrigation ditches, hand-dug with wooden or stone tools, appear to have been several miles long. Sometimes these ditches were chiseled through hardpan and even sandstone.

The Uinta Fremont Indians built small stone-and-adobe granaries, mortared with mud. They lived in small rock structures, with ten to twelve individual family dwellings making a village. Ruins in the Uinta Basin and elsewhere reveal that they constructed masonry buildings on the surface but also built stone-lined semisubterranean pit houses. Small villages were often situated along dependable water sources and near fertile land. On the Tavaputs Plateau, dry-laid masonry towers were built, probably for defensive purposes.

At the time of European expansion, beginning with Spanish explorers traveling from Mexico, five distinct native peoples occupied territory within the Utah area: the Northern Shoshone, the Goshute, the Ute, the Paiute, and the Navajo.

For several hundred years, the Fremont Indians inhabited the region, leading a semi-sedentary lifestyle, cultivating small plots of land, and creating or carving rock art on the smooth sandstone canyon walls.

Painted and carved symbols represent various aspects of their social activities, religious beliefs, worldview, and other aspects of their lifestyle. The rock art in Nine Mile Canyon is among the finest in the world, and scholars from many research institutions have traveled to the area to study, photograph, and marvel at it. Fremont Indian rock art, in significant part, remains a mystery to modern scholars and curious laymen alike.

Answers to why the Fremont people left the region are speculative at best and are topics of spirited debate among archaeologists; but, whatever the reason, the Uinta Fremont Indians began mysteriously abandoning the Uinta Basin as early as 1050 A.D, as much as 200 years earlier than other Fremont Indians disappeared from their homes in Utah.

The most significant Fremont cultural sites in the county are in Nine Mile Canyon on the Duchesne-Carbon county line. Archaeologists have identified and investigated nearly 300 archaeological sites in the Nine Mile Canyon area, with additional sites still occasionally being discovered.

A recent, extensive study by archaeologists indicates that the Tavaputs Fremont people adapted well to the Tavaputs Plateau's geography and natural resources. Late in arriving at the plateau country, the Tavaputs Fremont Indians adopted dry-laid masonry in the construction of their structures. They were also heavily concentrated in canyon drainages, which provided the best local environmental conditions for raising corn. They lived in the rugged Tavaputs Plateau country on a short-term or seasonal basis.

Euro-American Contact

The first historical contact between Euro-Americans and the Uintah Utes occurred with the Dominguez-Escalante expedition, which traversed the Uinta Basin and parts of Utah in 1776. Catholic friar Francisco Atanasio Dominguez led the party, assisted by Fray Silvestre Velez de Escalante. Because Escalante kept the expedition's journal, his name has gained greater fame than that of Dominguez. The small party consisted of the two priests and eight other Spaniards, including Don Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, the cartographer or mapmaker for the expedition.

The Dominguez Escalante expedition planned to leave Santa Fe on July 4 but was delayed for several weeks, including one due to Father Escalante's illness. Later in July, the expedition began its historical trek to Utah and the Great Basin.

The expedition's goals were to open a northern route from Santa Fe to newly settled Monterey, California, and to contact friendly Ute Indians along the way who might be ready for conversion to Christianity and Spanish ways of life. Other Spaniards had previously attempted to take a more direct route westward through Arizona, but the deserts and the hostile Indians made the Arizona route difficult and hazardous at best.

The expedition members also explored northwest from Santa Fe into southwestern Colorado and southeastern Utah. Earlier, in 1765, an enterprising Spanish trader or military reconnaissance man, Juan Maria de Rivera, had led a small group to southwestern Colorado and southeastern Utah. Except for the Rivera expedition, no other possible pre-Dominguez-Escalante expedition to southern Utah left known written records.

The Dominguez-Escalante expedition left Santa Fe and traveled north through southwestern Colorado, following streams and rivers. The expedition eventually reached the Gunnison River. After becoming lost and discouraged, they encountered a friendly Ute encampment. Here, they hired two Ute boys, whom the padres called Silvestre and Joaquin. These youths agreed to guide them to Utah Lake and the home of the Laguna (Uintah) Utes.

By September 16, the expedition had crossed the Rio de San Buenaventura (Green River) near the present-day town of Jensen, Utah. It is interesting to note that they killed buffalo in both the Colorado and Utah portions of the Uinta Basin. After crossing the Green River, the party journeyed up the Duchesne River, traveling in a westerly direction. The padres noted that the Indian boy Silvestre showed great fear after seeing the tracks of other horses and smoke from nearby fires.

Silvestre informed the padres that enemy Indians, "Comanches" as Escalante as he called them, were in the area. The "Comanches" were most likely a small group of Shoshone hunters who frequented the Uinta Basin from southern Wyoming or southeastern Idaho. Farther west in today's Duchesne County, the expedition witnessed more smoke. Silvestre was less fearful of these wisps of smoke, believing the people in the area were either Comanches or some Lagunas who usually came hunting here.

Information gained from the Dominguez-Escalante expedition indicates that the Uinta Basin in 1776 was used by both Ute and Shoshone Indians and that there was hostility between the two tribes. Hostility between the two tribes was probably a result of competition for hunting grounds, including those of the Uinta Basin.

Near the confluence of the Duchesne and Uinta rivers, the Catholic friars wrote that they "saw ruins of a very ancient pueblo where there were fragments of stones for grinding maize, of jars, and pots of clay. The pueblo's shape was circular. Modern researchers of the Dominguez-Escalante Trail have been unable to locate this ancient pueblo, which was most likely located near the Duchesne-Uintah county line.

On September 17, 1776, the expedition camped about twenty miles east of Myton, calling the campsite La Ribera de San Cosme. The next day, they traveled west to the junction of the Strawberry and Duchesne rivers (called by them Rio de Santa Catarina, de Sena, and Rio de San Cosme) and camped for the night in a meadow about a mile above the present-day town of Duchesne.

Reporting on the land seen that day, Escalante wrote: "There is good land along these three rivers [the Strawberry, Lake Fork, and the Duchesne] that we crossed today, and plenty of it for farming with the aid of irrigation—beautiful poplar groves, fine pastures, timber and firewood not too far away, for three good settlements."

Following the Strawberry River upstream, they camped the next night, September 19, near present Fruitland, and the next day crossed Current Creek and continued their journey westward. When the expedition reached the Strawberry Valley, approximately where Strawberry and Soldier Creek reservoirs are now located, Silvestre informed the padres that some of his people had lived there earlier, but had withdrawn out of fear of the "Comanches."

The expedition left the future Duchesne County, traveled through Strawberry Valley, descended Diamond Fork to the Spanish Fork River, and entered Utah Valley on September 23, 1776. There, the expedition members found the Utes very friendly and, after visiting for several days, the padres promised to return the following year to build a settlement. Utah history would have been different had the padres returned. Catholic missions rather than Mormon chapels might have dotted Utah's landscape.

Additionally, if Brigham Young had received this report about the area, perhaps Duchesne County's history would read very differently today, and the area might never have become part of the Ute Indian Reservation.

Father Escalante's expedition visited the Uinta Basin in September 1776. Between 1822 and 1840, French Canadian trappers Étienne Provost, François le Clerc, and Antoine Robidoux entered the Uinta Basin via the Old Spanish Trail, where they made their fortunes by trapping the numerous beavers and trading with the Uintah tribe. The Northern Ute Indian Reservation was established in 1861 by presidential decree. The United States opened the reservation for homesteading by non-Native Americans in 1905. During the early decades of the twentieth century, both Native and non-Native irrigation systems were constructed, including the Uinta Indian Irrigation Project, the Moon Lake Project, and the Central Utah Project.

Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City was founded on July 24, 1847, by a group of Mormon pioneers. The pioneers, led by Brigham Young, were the first non-Indians to settle permanently in the Salt Lake Valley.

The History of Utah is an examination of human history and social activity in the state of Utah, located in the western United States. Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest habitation of Native Americans in Utah dates back to approximately 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

Over the next several years, disagreements between the U.S. government and the Mormon leaders kept Utah from becoming a state. It wasn't until January 4, 1896, that Utah was admitted as the 45th state. The 1860s marked a period of progress for the state, as Utah became more connected to the rest of the country.

Utah enters the Union. Six years after Wilford Woodruff, president of the Mormon church, issued his Manifesto reforming political, religious, and economic life in Utah, the territory was admitted into the Union as the 45th state. In 1823, Vermont-born Joseph Smith claimed that an angel named Moroni visited him and told him about ancient Hebrew.

Who named the state of Utah?

It was created by the Compromise of 1850, and the city of Fillmore, named after President Millard Fillmore, was designated the capital. The territory was named Utah after the Ute Native American tribe. Salt Lake City replaced Fillmore as the territorial capital in 1856.

What was the original name of the state of Utah?

The Deseret State. When the Mormons first came to the territory, they named the area The State of Deseret, a reference to the honeybee in The Book of Mormon. This name was the official name of the colony from 1849 to 1850. The nickname "The Deseret State" refers to Utah's original name.

Utah was Mexican territory when the first pioneers arrived in 1847. Early in the Mexican–American War, in late 1846, the United States took control of New Mexico and California. The entire Southwest became U.S. territory upon the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, February 2, 1848.

The First Native Americans in Utah

Humans have been living in the area now known as Utah for at least 12,000 years. Among the first arrivals were the Apache, who descended from Canada to settle in Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico. The Apache eventually split into several groups, including the Navajo Nation (Diné).

At around 400 A.D., ancestral Puebloans—referred to as the Anasazi, or "enemy," by the Navajo—arrived from south of the Colorado River. They relied, in large part, on farming and settled in communities with large apartment-like dwellings built into the cliffs or valley floors. Between 1200 and 1400, climate change, crop failures, and the invasion of Numic-speaking (Shoshonean) people drove the Puebloans out of Utah and into Arizona and Nevada.

The Numic people began settling in Utah around 800 A.D. and evolved into four distinct groups based on their location: the Goshute (Western Shoshone), Northern Shoshone, Southern Paiute, and Ute. The first three groups were relatively peaceful hunter-gatherers. The Ute adopted the horse-and-buffalo culture of the Indigenous peoples of the Plains. Notorious for raiding, they partnered with the Spanish to campaign against the Navajo and Apache and traded captured Southern Paiute and Navajo people as slaves. After the Navajo arrived in Utah around 1400, Ute raiders drove them out by the mid-1700s.

Native American Reservations and Land Cessions

In 1776, European explorers and trappers traveled through what is now Utah and established trade relations with the Indigenous peoples. When the first Mormon settlers arrived in 1847, they believed that Indigenous people were "Lamanites," a group that they say left Israel in 600 B.C. and settled in America. According to Mormon teachings, Lamanites were punished with dark skin for disobeying God and needed to be rehabilitated by the Mormon church.

As Mormon settlements began to expand, they displaced Indigenous people. Many Native Americans died of disease and hunger, leading to battles between settlers and Indigenous people in the 1850s and 1860s. The conflict was resolved when the United States government established treaties with Indigenous people that terminated their land claims and attempted to move them to reservations between the 1860s and the 1880s.

Ute Wars

The Ute Nation rose episodically against the whites. Mormon settlers were relentlessly overtaking Ute lands and exhausting their resources and wildlife. Seeing that the Mormon intrusion was worsening, some of the Utes precipitated a series of forays on their settlements. This was known as the Walker War (1853), which led to orders from President Abraham Lincoln to relocate them to the Uintah Valley Reservation. The Ute Black Hawk War (1865-1868) erupted on account of the disruption white encroachment inflicted on ecosystems on which Native American populations depended.

Indians began to steal cattle from the settlers to stave off starvation. Hungry natives rallied around a young Ute firebrand, Black Hawk, who had been provoked into killing five Mormons, then escaped with hundreds of cattle. He galvanized members of the Ute, Paiute, and Navajo tribes into a loose alliance committed to pillaging Mormons across the region. After a protracted struggle that brought exhaustion to both sides, a peace treaty was signed in 1868.

In Colorado, the Meeker Massacre marked the final Ute outbreak (1879). Indian agent Nathan Meeker appeared on the Ute White River Reservation in 1878, resolved to transform the horse-loving resident Ute Indians from so-called "primitive savages" to hand-to-the-plow, pious farmers. Meeker ordered a Ute's pony racetrack to be plowed – the final straw. The Indians retaliated. Meeker and the 10 men employed by the agency were rubbed out, the agency was burned to the ground, and Meeker's family was captured and held hostage for two weeks. The cry, "The Utes must go," was heard throughout Colorado. The tribe was forced to sign a treaty and then relocate to the Ouray reservation in Utah.

The 1887 Dawes Severalty Act established private farms for Indigenous people on their territory across the United States and sold whatever remaining land to white settlers. Native Americans in Utah rejected the plan, which served to break up reservations. By the 1930s, 80 percent of reservation land had been sold to individuals.

In the 1950s, the government terminated Native American groups in Utah, and the groups lost control of their small slice of the remaining land. Beginning in the 1960s, the United States government paid out settlements to Native American tribes in Utah for violations of treaty agreements, and the Indigenous population began to grow.

As of 2022, approximately 60,000 Native Americans live in Utah, belonging to more than 50 tribal nations. Eight nations are federally recognized, including the Navajo Nation, the Northwestern Band of Shoshone Nation, the Confederated Tribes of Goshute, the Skull Valley Band of Goshute, the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, and the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah.

Utah Exploration

Among the first Europeans to visit Utah were Spanish explorers seeking treasure in the mid-1700s. Guided by members of the Ute tribe, Spanish Franciscan friars Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante traveled from Colorado to the Utah Valley in 1776, intending to return and settle the area, as well as convert the Indigenous peoples to Christianity. Their group mapped large parts of the American Southwest, opening it up to future settlement.

French-Canadian, American, British, and Canadian trappers and traders, such as Jim Bridger, Francois Leclerc, Étienne Provost, Antoine Robidoux, and Miles Goodyear, ventured into Utah's Great Basin in the 1820s and 1830s. In the 1840s and 1850s, surveyors working for the United States government—such as Kit Carson, John Charles Fremont, Howard Stansbury, and John Gunnison—mapped Utah for future settlement.

Polygamy to Statehood

Another constitutional convention met in 1862 and petitioned for statehood. Congress responded by rejecting the petition and passing the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, which prohibited polygamy in United States territories and disincorporated the LDS church. Throughout the 1860s, the Utah Territory's borders shrank as Colorado's territory expanded. Nevada, Idaho, and Wyoming were organized.

On May 10, 1869, the first transcontinental railroad was completed when the Union and Central Pacific Railroads met at Promontory Summit in the Utah Territory. New settlers to the Utah Territory, many of whom were not Mormon, and tensions between the groups began to build.

The Supreme Court upheld the anti-polygamy law in 1879, although the practice continued in Utah. A series of acts prohibited practitioners of polygamy from voting or holding public office and allowed the federal government to take LDS lands. The federal government arrested many polygamist men, and some polygamist families went into hiding.

In 1890, the LDS church officially renounced polygamy, opening Utah's path to statehood. After meeting several requirements to become a state, including officially banning polygamy in the state constitution, Utah became the 45th state admitted to the Union on January 4, 1896.

After decades of lobbying, Utah became the 45th state on January 4, 1896. First settled in 1848 by Latter-day Saints fleeing religious persecution, the isolated settlement quickly developed into a thriving commercial center. The completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad at Promontory Point, Utah, in 1869 drove even more traffic to the territory, as Mormons from Europe and the East Coast, as well as hopeful miners, traded in handcarts for train cars. Together, they made Utah their home.

Despite its growth from 11,000 in 1850 to over 210,000 just four decades later, Utah remained notorious. After the Supreme Court condemned the then-common Mormon practice of plural marriage in 1879, the federal government began enforcing the decision. Anti-polygamist raids became routine; many Mormon husbands soon found themselves behind bars. Only when LDS Church President Wilford Woodruff publicly condemned polygamy starting in 1890, was Utah statehood granted.

Fur trappers were among the first African Americans to settle in Utah in the 1820s. Several Black slaves were among the first group of Mormon settlers who arrived with Brigham Young in 1847. Several free Black Mormons were among the early Mormon settlers, although they were prohibited from voting, holding office, and marrying white people. While Young declared that the Mormon religion permitted slavery, several LDS leaders strongly opposed the practice. Some Mormons even bought enslaved Native American children to save them from slavery and convert them to the LDS church.

The Compromise of 1850 allowed Utah to decide whether to become a slave state or not. The Utah legislature sanctioned slavery in 1852, and the legislature decreed that slaves who were abused by their slaveholders could be freed. But very few were freed before Congress abolished slavery in the territories in 1862. During the Civil War, Utah didn't send troops to either side.

The Black population increased in the state through the end of the century—and with it, as in many other places throughout the United States, discrimination. Following the civil rights movement, the priesthood in the LDS church opened to people of all races, including African Americans, in 1978.

Non-Mormons began arriving in Utah with the completion of the new transcontinental railroad in the late 1860s and continued through the 1870s, including Chinese construction workers who helped build the rails, as well as Irish, Cornish, and Welsh miners. Immigrants from southern and eastern Europe arrived in the 1890s and during the early decades of the twentieth century, and Greeks, Italians, Slavs, Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans, and other ethnic groups further enriched Utah's cultural fabric and worked in the railroad and mining industries.

Other waves of immigrants came throughout the 20th century, including Mexicans in the early part of the century and numerous refugees from Southeast Asia in the 1970s and 1980s.

The prime problem of the 1870s was overpopulation. A new generation had grown up and had to find ways to make a living. Some worked in mines, others on railroads still under construction, and others migrated to Idaho, Colorado, Nevada, Wyoming, and Arizona.

In the remaining years of the nineteenth and early years of the twentieth century, new colonies were founded in a few places that could be irrigated: the Pahvant Valley in central Utah (Delta, 1904); the Ashley Valley of the Uinta Basin in northeastern Utah (Vernal, 1878); and the Grand Valley in southeastern Utah (Moab, 1880).

However, most of these "last pioneers" had to seek a home in surrounding states where land was still available—such as Nevada, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Arizona—or even in Alberta, Canada, and northern Chihuahua and Sonora in Mexico. There was no longer the mobilization by ecclesiastical authorities of human, capital, and natural resources for building new communities that had characterized earlier undertakings.

The migrations were mainly sporadic—unplanned by any central authority. However, two colonizing corporations organized with ecclesiastical participation were the Iosepa Agricultural and Stock Company, which founded a Hawaiian colony in Skull Valley in 1889, and the Deseret and Salt Lake Agricultural and Manufacturing Canal Company, also established in 1889 to promote settlement in Millard County. The church financially assisted these companies, held a significant block of stock in each, and ensured they would be managed for the community's benefit.

Another factor in the decline of colonization, particularly after 1900, was the abandonment of the concept of “the gathering,” under which converts were urged to gather to “Zion” to build the Kingdom of God in the West. Converts were now urged to stay put and build up Zion where they were.

The Uintah Basin

The story goes that in 1861, Brigham Young sent an exploring party to the Uinta Basin to assess the region's potential for Mormon settlement. Upon the expedition's return to Salt Lake City, its members reported in the Deseret News of October 25, 1861, that they had found "the fertile vales, extensive meadows, and wide pasture range so often reported to exist in that region, were not to be found, and that the country is entirely unsuitable for farming purposes."

The exploring party found the region lying east of the Wasatch Mountains a "vast contiguity of waste, measurably valueless excepting for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians, and to hold the world together." The report was disappointing to Brigham Young and others. Reports from trappers and hunters earlier had described the Uinta Basin with unreserved praise, claiming that it was a beautiful valley and more to be desired than any they had seen in the Great Basin, not excepting that of Great Salt Lake.

The expedition's survey of the Uinta Basin was likely limited, and it did not extend farther east than what is now called the Myton Bench. Ironically, the Myton Bench today is a significant farming region of the Uinta Basin; in fact, much of the region surveyed by the 1861 expedition remains a productive agricultural area. The change in land productivity has occurred as a result of the human will to turn a "vast contiguity of waste" into a productive farming and ranching region.

The land of Duchesne County, Utah, has long been inhabited by the Ute Indians; white interest in the Uinta Basin, beginning with the Dominguez and Escalante Expedition of 1776, has waxed and waned for more than two centuries. Soon after the 1861 expedition's report to Brigham Young, much of the Uinta Basin and all of present-day Duchesne County were set aside as an Indian reservation by President Abraham Lincoln.

From the 1860s until the turn of the century, the Ute Indians and their reservation were largely left undisturbed, protected in part by the region's geographical isolation.

However, changes in federal Indian policy in the 1880s, the discovery of Gilsonite, the increasing demand by whites for virgin farm and grazing lands, and an interest in area water by Wasatch Front communities brought increased white attention to the western portion of the Uinta Basin.

Uintah has come to be spelled two different ways, depending on its usage. Uinta spelled without the "h" indicates a natural or geographical feature, such as the Uinta Mountains or Uinta Basin. Uintah, spelled with the "h," means a cultural or human creation; for example, Uintah County or Uintah Basin Medical Clinic. Early chroniclers and narrative writers did not always make these distinctions, and the reader will find some examples of what at first glance might seem inconsistent usage, but which have been retained in their original form for the sake of historical accuracy.

The Uinta Mountains and Uinta Basin are part of two larger physiographic regions identified by geographers as the Rocky Mountain and Colorado Plateau provinces, respectively. The Uinta Mountains are the region's dominant feature, forming the northern rim of the Uinta Basin. The Uintas are a rugged range of mountains that trend east-west, unlike most mountain ranges, which run north-south. The Uinta Mountains are about 150 miles long and 30 miles wide.

The central core of this broad range of mountains was formed by the sedimentation of mainly quartzite strata, more than 20,000 feet thick, laid down by ancient oceans over the course of hundreds of millions of years. During much of that time, a significant part of the area that would become the western United States, including future Duchesne County, was covered by seas.

At other times, the seas subsided or the land rose, leaving dry land, some of which was walked by dinosaurs some 100—150 million years ago. Throughout this time, sediment deposition continued, either from the oceans or from soil or sand washed down or blown in from neighboring highlands.

The Uintas are the highest range in Utah, with several peaks over 12,000 feet; the highest, Kings Peak, is 13,528 feet above sea level.1 Unlike many other mountains in the state and the region, the Uinta Mountains lack igneous rock of any consequence; this explains why no significant ore deposits have been found there.

The Utes relate the story of Norita, also known as Sleeping Princess Mountain, which lies on the western end of the county, overlooking Rock Creek. To many, this mountain clearly resembles a woman lying on her back. Many people who first look at the mountain comment that it resembles the woman's silhouette in detail, from her face to her feet. The legend tells of an Ute maiden who was known throughout the region for her beauty and kindness. Enemy Indians, hearing of her great beauty, came to capture her. Upon seeing the enemy warriors, she fled to a high cliff.

The legend recounts an Ute maiden renowned throughout the region for her beauty and kindness. Enemy Indians, hearing of her great beauty, came to capture her. Upon seeing the enemy warriors, she fled to a high cliff. Rather than be captured, she jumped to her death. Due to her bravery, the Great Spirit sent wind and rainstorms, which carved the mountain into her likeness so she would be remembered by all who looked at the mountain.

The eastern rim of the Uinta Basin is formed by the Rocky Mountains of western Colorado. The massive Uinta Basin is approximately 125 miles long and ranges in width from 40 to 60 miles. 4 The rivers and streams of the Uinta Basin are its lifeblood in addition to serving as important transportation corridors. The historically significant Dominguez and Escalante expedition of 1776 followed the Duchesne and Strawberry rivers through much of the Uinta Basin and future Duchesne County to reach Utah Valley.

The Green River provided the means for William Henry Ashley and John Wesley Powell, among many others, to gain access to the Uinta Basin from Wyoming. The rivers and streams of the county and of the Uinta Basin attracted many fur trappers and traders to trap and trade for beaver pelts beginning in the 1820s. And, at the turn of the twentieth century, water from the untapped streams of Duchesne County was highly sought after by farmers and ranchers from Utah County and the Wasatch Front.

Legends of Spanish mines bolster the likelihood that other Spanish exploration parties reached the Uinta Basin and Duchesne County before the 1820s, when Mexican, English, French, and American fur traders began trapping and trading for beaver.

Local stories recount the Spanish discovery of gold and the forced labor of Indians in the mines of the Uinta Basin. According to several leg ends of the Utes, the oppressed workers eventually rebelled and killed all the Spaniards. This local lore is bolstered by claimed discoveries of cannonballs, bridle bits, old diggings, rock smelters, rusted Spanish helmets and breastplates, as well as tree and rock inscriptions.

However, no scholarly confirmation from written records or studies of extant Spanish artifacts, presumably Spanish diggings, and smelter works has yet confirmed the local lore of Spanish presence and the development of gold mines. Like much of the lore of the Spanish in the West, Duchesne County has tales of lost treasure and gold, which, if found, would make the discoverer fabulously wealthy. The continued life of these stories of gold and lost Spanish mines makes for lively conversations at summer campfires and at family dinner tables.

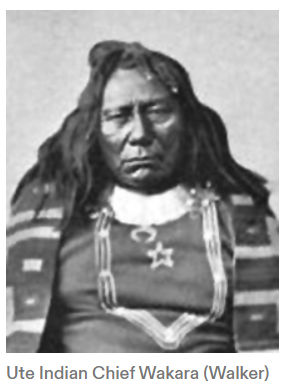

Closely related to lost Spanish gold mines is the county's most famous gold story—the Lost Rhoades Mines. A standard version of the story tells of Ute chief Wakara, who went to Brigham Young shortly after the Mormons arrived in the Salt Lake Valley.

“For every ounce of mined gold, gallons of blood have been spilt.”

Thomas Rhoades was commissioned as Brigham Young's representative to the Ute Chief Wakara. Chief Wakara allegedly accompanied Rhoades to the location of a fabulously wealthy mine, the wealth of which was to be used only to benefit the LDS church. Historians now discredit the story that the Ute Indians gave gold to the Mormon pioneers, and also allowed Thomas Rhoades, followed by his son Caleb, to mine gold from the Uintas for several decades.

Gale Rhoades spent most of his life following in the footsteps of his great-grandfather, Thomas Rhoades, attempting to find lost treasure. He made a living establishing illegal prospecting corporations using a gold nugget he claimed to have originated from the Uintas. Speculators would finance his attempts to find the gold based on his convincing evidence and his published book Faded Footprints: The Lost Rhoades Gold Mines & Other Hidden Treasures of the Uintas. Gale Rhoades died owing thousands of dollars to investors. Gale Rhoades was certainly a con man exploiting his relatives.

Thomas Rhoades, however, was described in his obituary in the Deseret News in 1890 as "a mighty hunter of grizzly bears."

In fact, Thomas Rhoades did deposit more gold for tithing than any other pioneer. Rhoades tithed so much gold that he was given a house next to John Taylor, Brigham Young, and Willard Richards. Where did he get around sixty pounds of gold worth $17,000? According to the church, it all came from Sutter's Mill; this is likely true. But much more gold was entering the Mormon Pioneer economy from undocumented sources.

The early history of Utah is incredibly incomplete. There is growing evidence that the Aztec empire did indeed extend far beyond the Four Corners area. Parowan Gap is certainly a Fremont Indian or Aztec site. Myths, legends, or facts could be unraveled with more study.

Current Utah high school textbooks begin with the accounts of friars Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante visiting the area in the late 1770s. However, actual records of the Utes and their interactions with the Spanish Empire date back to the early 1600s. There were over 240 years of Ute-Spanish relations that predated the arrival of the Mormon pioneers. The mystery of the Lost Rhoades Mines persists because the history is so one-sided.

Is there an Ute account of this same legend?

Chief Wakara was a highly successful leader because he learned to take advantage of the introduction of the horse. His band of Timpanogos Utes was one of the few Indian groups in Utah that were well-trained equestrians. They used horses to conduct seasonal migrations for hunting game and plundering enemies. Wakara carried a single-action shooter pistol at all times. Abandoning the popular wigwam shelters, Wakara and his tribe adopted the portable teepee.

“They were robbers of a higher order than those of the desert. They conducted their depredations with form, and under the color of trade and toll for passing through their country.”

John C. Fremont in 1844

Wakara, according to the legend, had been chosen by right of succession as the guardian of gold mines located in the Uinta Mountains. These gold mines had been made sacred by the forced labor and sacrifice of past generations of Ute Indians. In some of the accounts, the Spanish treatment of Utes was so brutal that the Utes revolted and drove the Spanish back to New Mexico. After some time — perhaps generations — the Spanish returned and forced the Utes to resume working the mines. This led to another revolt near Rock Creek sometime in the mid-1800s. As the story goes, all the Spaniards were killed and the mine entrances were buried.

The Mountain Men

Following the Dominguez-Escalante expedition of 1776, the next documented visitors to the Uinta Basin were Euro-American mountain men and fur traders, who began arriving in the 1820s. European men's fashion of the time required a steady supply of beaver to produce felt hats. The American fur industry and the American West provided the beaver pelts. The economic profit to be gained from exporting American beavers was an essential factor in America's interest in the American West.

After the famous Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804— 06, which explored the Pacific Northwest coastlands of the Louisiana Purchase, American fur trappers and traders, in search of furbearing animals, extended their search into the upper Missouri River country of Montana and the central Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. Included in their search for beaver was the area of the Uinta Basin.

It was during the 1820s and 1830s that mountain men discovered and explored many remote areas of the American West, becoming more familiar with secluded locations, including the Uinta Basin. The fur trade in the Uinta Basin was a significant chapter in the broader economic history of the fur trade, and at least one trading post was established near the Whiterocks River in what would become future Uintah County.

Deciding not to go any farther down the often wild river, Ashley cached some of his supplies and traded for some horses with some Utes, whom Ashley described as being well clothed in "sheep skin & Buffalo robes superior to any band of Indians in my knowledge west of Council Bluffs." Some of the Ute Indians also were "well armed with English fuseeze" guns.

The Uintah Utes, a band of Northern Utes, most likely had occupied the Uinta Basin sometime after the departure of the Dominguez-Escalante expedition and before extensive contact was made with the fur traders and trappers. Many of the Utes, including the Uintah Ute band, had acquired the horse and become expert horsemen. The Utes' acquisition of horses and guns from Spanish and later Mexican traders gave the Native Americans more power to deal with their neighbors, the Shoshoni, to take advantage of the unmounted Goshutes and other bands and tribes, and to expand their trade activities. Ashley noted that some of the Utes were adorned with seashells, suggesting an extensive trade system among Native Americans.

Now mounted, Ashley and his men traveled west, following the Duchesne River, which Ashley called the "Euwinty" River. Shortly after entering Duchesne County, Ashley sent out hunters to replenish the company's dwindling meat supply. The hunters were successful, and the company's meat supply was temporarily well-stocked.

Wakara supposedly was told in a dream that when the big hats (Americans) came, he was to tell them of the gold. The first Americans in the region—the mountain men—would not listen to him. When he said "Brigham Young," Young agreed that only one man would be chosen to go and get the gold, which was so pure that smelting was unnecessary. Knowledge of the gold's existence and location was to be a secret.

Thomas Rhoades was selected to get the gold. The gold was to be used exclusively by the Mormon Church and not to benefit any individual. The Ute chief warned that Rhoades would be watched while in the mountains and that no other would be allowed to come. If any others tried to do so, they would be killed. After a few years, Thomas Rhoades passed the responsibility to his son, Caleb, and, with Wakara's death in 1855, his brother, Aropene, assumed leadership and oversight of the mines.

According to legend, gold from the Rhoades mines was used by the Mormon Church to mint its gold coins and to plate the statue of the angel Moroni atop the LDS Temple in Salt Lake City. Although no known records exist in church archives, Brigham Young supposedly promised Wakara and Aropene, in the name of the Lord, that the gold would not be discovered by anyone and would be kept secret until the "last days," when it would come forth to benefit the Mormon church and the Utes in a time of great need.

Many of the folktales on the subject contain warnings of supernatural power and heavenly intervention, preventing anyone from finding the gold stores and mines. Other stories tell of people who have found one of the several mines and were suddenly stricken with heart attacks or other ailments, or were warned by ghostly Ute warriors to leave and never return.

Young and the other Mormon leaders also had a high opinion of Wakara. Young saw him as an intelligent man. The Utes were still reeling from the changes they had been adapting to over the past 300 years of Spanish domination.

The problem Wakara suffered was that his lifestyle relied on slavery and theft. Wakara's Utes would seasonally migrate to California—Mexican territory at the time—to steal cattle and horses from their Spanish/Mexican enemies. Wakara would also raid neighboring interior tribes such as the Paiutes and enslave their children. He would then trade his captives and animals in Santa Fe for food, ammunition, blankets, feed, and supplies.

Wakara must have understood the value of gold usage in currency. If he knew about Spanish gold mines or a former Aztec mine, one would wonder why Wakara wouldn’t exploit gold for currency?

But Wakara and other Indians did not culturally acknowledge personal property rights and land ownership. They called gold "yellow rock" then "money rock." Wakara initially gave away most of his land to Mormon pioneers, provided they would move onto the land, graze their animals, and grow crops. He wanted pioneers living there, because he knew they could put the land to good use. Wakara had a long-term vision for the land and his people. He recognized the value of integrating his people and adapting his culture to the modern world. He also knew that these more friendly white men would likely protect the Utes from their enemies. The nearly 300 years of incomplete Utah history, found scarcely in history books, were likely similar to what was more well-documented in South America. The Spanish were ransacking the regions and tribes for wealth in any form.

The Black Hawk War was fought between the Ute Indians and the Mormon settlers in central and southern Utah between 1865 and 1872. Tensions between the groups had been building since the Mormon settlers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 due to struggles over resources. The Mormon settlers chose the best land to settle, took productive fisheries such as Utah Lake, took timber, drove game away, and diverted critical water sources for irrigating crops, leaving the Native people of Utah destitute and starving. After almost twenty years of living together in relative peace, tensions became too much. No single event sparked the war, as skirmishes occurred on a small scale across central and southern Utah.

The Ute nation rose episodically against the whites. Mormon settlers were relentlessly overtaking Ute lands and exhausting their resources and wildlife. Seeing that the Mormon intrusion was getting worse, some of the Ute precipitated a series of forays on their settlements. This was called the Walker War (1853), which resulted in orders from President Abraham Lincoln to force them onto the Uintah Valley Reservation. The Ute Black Hawk War (1865-1868) erupted on account of the disruption white encroachment inflicted on ecosystems on which Native American populations depended.

However, many historians suggest that a disagreement between two men escalated into warfare in April 1865. A young Ute man named Jake Arapeen rode into Manti with Black Hawk and met up with John Lowry, a Mormon settler and employee of the United States Indian Office, to discuss the tensions. The discussion led to a heated argument between the two men. In anger, John Lowry pulled Jake Arapeen off his horse by his hair, and they fought on the ground. Seeing this as the lowest of insults, Jake Arapeen and Black Hawk rode off together, and that day decided an all-out war against the Mormons was the only option.

The fiercest of the fighting took place between 1865 and 1867. Both sides were perpetrators during this war, and sadly, most of the victims were innocent of depredations. The Circleville Massacre of April 1866 was one such horrible event to come out of the Black Hawk War. A friendly group of Paiute Indians was camped near Circleville when a church order came down to disarm the Indians.

The Mormon settlers were interested in self-preservation and so decided to round up the Paiutes and put them in a meeting house under security. Two Paiutes managed to break free and were shot as they were getting away. Paranoia got the best of the settlers, and they decided they should kill the twenty-four remaining Paiutes. Brigham Young was disgusted by the murders and "later said that the curse of God rested upon the Circle Valley and its inhabitants because of it."

Also in 1866, the Utes raided horses and cattle from Scipio and the surrounding area, totaling 350 head of cattle, a massive loss for Mormon settlers. As the settlers attempted to reclaim their cattle, the Battle of Gravelly Ford commenced. The Mormons and the Utes exchanged gunfire, killing a 14-year-old Mormon boy and James Russell Ivie. During the battle, Black Hawk was shot in the stomach, but the Utes managed to escape.

In 1867, Black Hawk was sick from an infection caused by the bullet wound he received in the Battle of Gravelly Ford. He saw that his people could not win the war as the Mormon population kept increasing. Black Hawk decided to embark on a campaign of peace. He personally visited many Mormon villages he had raided to apologize for the pain he and his warriors caused. He was laid to rest on September 27, 1870, in the same place as his birth: Spring Lake, Utah.

The death of Black Hawk did not bring an end to this war. The Ute people were starving, their population decimated through disease and loss of game. Periodic raids were conducted by the Utes to avoid starvation until 1872. In 1872, the federal troops took control of the area as the Nauvoo Legion was disbanded. The federal troops strictly enforced the Utes' removal to the Uintah Reservation. Once the Mormon settlers were free from raids, they were able to go back to previously abandoned settlements. They also used Chief Black Hawk's raiding trails to expand their territory even further.

The historical marker needs an update, as we now know that the number of settlers killed was at least 70. It is thought that at least 140 Native Americans died during this conflict, likely more. The result of the war for the Utes was a move to the Uintah Reservation, giving up their traditional lifestyle for a life of dependency on the United States Government. The result of the war for the Mormon settlers was the unimpeded colonization of the Utah Territory, which ultimately led to statehood in 1896.

The Reed Trading Post and Fort Uintah

The Uinta Basin became an important crossroads for fur trappers, traders, and overland travelers. To take advantage of the growing fur trading and trapping activities of northeastern Utah, Kentuckian William Reed, his nephew James (Jimmy) Reed, and Denis Julien established the Reed Trading Post in 1828 near the confluence of the Whiterocks and Uinta rivers. The Reeds operated the post until 1832, when Antoine Robidoux purchased the business and location from them. The Reed's enterprise was the first fixed Euro-American economic enterprise in the Uinta Basin and in Utah. Other trading posts and permanent outposts were later established in Browns Hole and on the Ogden River near present-day Ogden.

The relationship between the Ute Indians living in the Uinta Basin and the Mexican, American, British, and French-Canadian newcomers was, for a time, cordial if not friendly. However, as the whites' presence expanded, disputes occasionally arose between the Ute people and their new neighbors. On one occasion, a California Indian, probably on a trading expedition to the Green River country, was believed to have stolen one of Robidoux's prized horses. Robidioux asked another visitor, Christopher "Kit" Carson, to track down and retrieve the stolen horse. Carson and his partner, Stephen Louis Lee, had journeyed to Ashley Valley to trade with the Utes but had found that Robidoux had already acquired the bulk of the furs trapped that season.

Carson agreed to help find the missing horse. The tracks of the horse and its apparent thief headed west. After two days of tracking the horse and the California Indian, Carson located the missing horse and its new owner in what was likely eastern Duchesne County. A fight ensued, and Carson killed the Indian.

Other important figures, including fur trappers, government explorers, overland travelers, and Indians, visited the Uinta Basin in the 1830s and 1840s. In 1834, Warren A. Ferris, while employed by the British Hudson's Bay Company, spent several weeks in the Uinta Basin trapping and hunting. Ferris avoided camping near Fort Robidoux and instead set up a temporary encampment on a benchland that was likely near present-day Altonah. Ferris wrote:

"Our camp presented eight earthen lodges, and two constructed of poles with cane grass, which grows in dense patches to the height of eight or ten feet, along the river Lake Fork? Our little village numbers 22 men, nine women, and 20 children; and a different language is spoken in every lodge, though French was the language predominant among the men, and Flat-head among the women."

Ferris noted the basin's streams and abundant game but strangely neglected to mention Antoine Robidioux's trading post on the Whiterocks River. Although he was favorably impressed with the area, Ferris did not remain long and never returned to the Uinta Basin.

During its existence, several notable visitors stopped by Robidoux's trading post. Several months before Robidoux finally was forced to abandon the Uinta Basin in 1844, topographical engineer and U.S. Army captain John C. Fremont and his expedition paid a brief visit to the Uinta Basin. A year earlier, Fremont and a thirty-man expedition, which included guides Thomas Fitzpatrick and Kit Carson and cartographer Charles Preuss, were ordered west to conduct further surveys of the western interior.

When the Nine Mile Road was completed at about the same time Fort Duchesne was established in 1886, ranchers and settlers claimed land along the thirty miles of Nine Mile Canyon. A few ranchers had wandered into the area a few years earlier, but most came when the road was built and improved.

The center point, socially if not geographically, was Brock's Ranch, located at the mouth of Gate Canyon. Here, the army established a relay station for the telegraph line, manned by soldiers from Fort Duchesne. Brock's Ranch was also the last campground with good water before leaving the canyon and traveling towards Smith Wells.

This Brock, whose first name is unknown, was one of the first ranchers in the Nine Mile area, but within a short time of settling there, he killed a man named Foote in a dispute and fled the country. His place was taken over by Pete Francis, who opened a saloon and a twenty-five-room hotel. Shortly after the establishment of several new businesses, Francis was shot and killed in a gunfight in his own saloon in 1901.

In 1892, Indian agent Robert Waugh and the Indian Office in Washington, D.C, agreed that Strawberry Valley should be leased to ranchers of the area. Their rationale was twofold: first, the Utes did not have sufficient stock to utilize the grazing grounds fully; and second, attempting to prevent trespass was virtually impossible without incurring additional expenses or resorting to military intervention. Waugh and others reasoned that if Strawberry Valley were leased to neighboring livestock men, the leases would ensure that Strawberry Valley would be kept free of transient cattle herds and other trespassers while at the same time raising money for the federal treasury.

Soon after Nutter obtained his lease, other grazing interests, specifically sheepmen, sought grazing leases from the Ute Tribe. For several decades, sheep and wool production had grown steadily in the state of Utah. As a result, there was keen competition between sheepmen and cattlemen for the little remaining virgin summer grazing grounds found in the eastern part of the state.

The leasing of grazing land by the Ute Indian agent to sheepmen greatly disturbed Nutter. Like many other cattlemen of the time, Nutter viewed sheep and cattle as being incompatible on the same rangeland. In Nutter's view, sheep destroyed grasslands. Rather than risk a range war, Nutter moved his cattle to Nine Mile Canyon and the rangeland of the Tavaputs Plateau after his lease expired, and in 1902, he bought the Brock Ranch from the widow of Pete Francis.

Nutter had little or no interest in running either a saloon or a hotel, and he converted the hotel into a bunkhouse for his cowboys. Cowboying was not always a lucrative profession; occasionally, some cowboys did other kinds of work, which, from time to time, filled their pockets with more money than did their skills working cattle. Virginia Price, Nutter's daughter, explained:

"Between train and bank robberies, the outlaws often turned to rustling. Like a lot of other ranchers, Nutter often found it more practical to hire the outlaws to work as cowhands during their cooling-off periods. Most of them were cowboys at one time or another and made top hands, but what was more important, their code prevented them from rustling from an employer."

Nutter's ranch headquarters was more than a collection of buildings and cattle. When he bought the Ranch, he also acquired a lone peacock left by Mrs. Francis Nutter.

At the peak of Preston Nutter's cattle operation, his cattle ranged across public lands from Blue Mountain on the Colorado-Utah border to the west Tavaputs Plateau, and south to the Arizona Strip in extreme northwestern Arizona. He owned several thousand acres in the bottoms of Nine Mile Canyon as well as on the mountains to the south and east of the canyon. On this sprawling Ranch, Nutter ran upwards of 25,000 cattle, making him one of the most prominent cattle barons in Utah at the turn of the century.

Nutter continued raising cattle, operating out of his Nine Mile Canyon base for the next several decades. He had gained such notoriety and high regard that he was a consultant to Washington politicians on grazing issues and was a firm supporter of federal regulation of livestock grazing. Preston Nutter died in 1936; the Ranch continued in operation under the direction of his daughter, Virginia Nutter Price.

Outlaws

Other nefarious characters used the Uintah Indian Reservation for their own illegal purposes. Robert LeRoy Parker, alias Butch Cassidy, and his gang of outlaws known as the Wild Bunch commonly traveled through Nine Mile Canyon en route from Price to the Strip, Vernal, or Browns Park. Many local tales are told of Butch Cassidy and other outlaws visiting, eating with, and being warned of coming lawmen by ranchers and homesteaders along Minnie Maud Creek.

One such story, told years later, recounts how Butch and some of his men came to the Nine Mile homestead, where Mariah "Ma" Warren lived. The outlaws frequently stopped there while riding through the area and often traded trail-weary horses for fresh ones. On one such visit, Ma Warren gladly prepared a meal for the travelers before they departed.

The travelers made camp for the night a mile or two from Warren's place. No sooner had they gone than a posse from Carbon County came asking about the outlaws. Ma Warren claimed not to have seen or heard the outlaws. Following western courtesy, a meal was offered to the posse members. While cooking her second meal of the evening, Ma Warren had one of the children finish the cooking chores. She slipped out the back door to the corral where she quickly bridled a horse and rode bareback a mile or two to the camp of Cassidy to warn him of the lawmen's presence. She then returned in time to serve the unsuspecting posse their meal.

Indian Reservation

In 1861, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the executive order creating the Uintah Indian Reservation in Uinta (Duchesne) Valley to house relocated Ute Indians, the reservation was part of a federal policy of separating Indians from whites. This formal ethnocentric policy of the federal government was rooted in earlier English colonial policy, as outlined in the Proclamation of 1763, which distinguished between Indian territory and white territory in the British colonies in North America.

The policy also attempted to prevent individual whites as well as individual colonies from dealing with the Indians politically and economically. All relationships with the Indians were to be conducted through the British crown.

A similar policy was adopted with the election of Andrew Jackson as president. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 attempted to remove all Indians east of the Mississippi River to the newly formed Indian Territory located west of the Mississippi. Over several decades, Indian territory shrank to much smaller areas and became increasingly isolated, with the creation of reservations. The purpose of these policies—formal or informal—remained the same, however: to remove and isolate Indians from the march of white civilization and prevent conflicts between the two cultures.

Ute Indians and others from Mormon settlements were not a high priority with federal officials in the tumultuous decades leading to the Civil War. As elsewhere in the West, conflicts arose when Mormon settlers occupied the lands of the Ute, Shoshoni, Goshute, and Paiute. As discussed, territorial governor and superintendent of Indian Affairs, Brigham Young, early on attempted to establish a similar program of segregation of the Indians from expanding Mormon settlements. Young's Indian farm system failed in part because of a lack of federal government support.

President Lincoln replaced Brigham Young's Indian farm system with the Uinta Valley Indian Reservation. Eventually, most of the Ute Indians from along the Wasatch Front and central Utah were forced to relocate to the new reservation. For Mormon settlers, the threat of conflict was removed, and unlimited access to the land and other resources was achieved. The Uintah Reservation did, for a time, effectively separate and isolate the two cultures.

The reservation program attempted to teach the Ute people the ways of the whites. But neglect by the federal government, some mismanagement of the reservation, dishonesty among Indian agents and others, and forced confinement wrought havoc among the Ute people, much as reservation life did among other Indian tribes in the West. The death rate soared, poverty was widespread among Indian families, and, in general, life for the Utes on the Uintah Indian Reservation was miserable.

Added to the general despair of the Ute people was increased pressure from their white neighbors to acquire more of their land and water. The Ute people were not successful in adopting white culture in isolation, and their situation was typical of life on other reservations.

Deplorable living conditions at reservations and the rapid decline of the national Indian population gave rise to several Indian reform groups, located primarily in the eastern United States. Foremost among those calling for reform was Helen Hunt Jackson, whose book Century of Dishonor outlined the plight of the Indians and predicted that Native Americans under the reservation system were not going to survive into the twentieth century. l Equally concerned with the growing "Indian question" were eastern Protestant churches, which called for reforming the ailing Indian reservation system.

Representatives from these reform groups and various churches came together at Mohonk Lake, New York, beginning in the late 1870s to find a solution to the Indian problem. Meeting annually, the reformers eventually adopted a plan.

At the core of the Indian problem, as they saw it, was the reservation system and the collective control of land by the various tribes. This ran counter to the self-sufficiency and individualism preached and practiced by white Americans. To rectify the problem, the Mohonk Lake conference attendees called for a complete elimination of Indian reservations. Indian tribes would no longer be recognized, and reservations would be replaced with individual land ownership, which would encourage individuality. This would force assimilation of the Indians into white society.

Homesteading the Uintah Reservation

After white settlers came to Utah, their way of living and the Utes’ way of living just didn’t work together. Before too long, the settlers were demanding that the government get the Utes out of the way. So President Abraham Lincoln created a reservation in the Uinta Basin in 1861. Most northern Utes were forced to move from their traditional lands and go to the reservation.

In the 1880s the government created the Ouray Reservation south of the Uintah Reservation and moved Utes from Colorado to both reservations. But the Utes did not even get to keep these arid regions. In the early 1900s, the U.S. government decided to make the Indians into farmers. They gave members of the three tribes individual parcels of land.

They then took parts of the reservation lands to create the Uinta National Forest and Strawberry Reservoir.

After that, they threw open the rest of the reservation to white homesteaders. This left a much-reduced and disjointed Uintah-Ouray Reservation, which shrank from almost four million acres in 1882 to about 360,000 acres in 1909.

By the summer of 1905, Indian Office and U.S. Land Office officials had completed all the necessary preparation to open the Uintah Indian Reservation to homesteading. Over 111,000 acres had been allotted to Indian families. Another 282,560 acres were reserved for hunting, grazing, and other resource development for the Ute people, with much of it located in the Deep Creek area. The reserved Indian grazing ground also helped protect and guarantee water for the numerous Indian homesteads. In addition to Indian homesteads and grazing grounds, 60,160 acres were reserved for reclamation purposes.

The opening of the Uintah Indian Reservation was a welcome opportunity for Utah Valley farmers, who had long coveted water from the Strawberry River. They had prepared a water plan similar in nature to the earlier, successful but legally questionable transmontane water-diversion system built by a group of Heber Valley farmers.